I’ve had a bit of blogger’s block lately (read: the last two years). I have a tendency to write half of a blog post and then scrap it because I don’t think it’s that interesting. Well, my goal this year is to get over it. So to start I decided I want to highlight some of the very cool science my friends did in 2018. Honestly I feel like I don’t do enough to lift up my friends and celebrate their accomplishments, so here are three examples of papers my friends wrote last year that sparked a change in the way I think about one topic or another. I should say, if you aren’t keeping up with these early career researchers, you’re simply missing out on some great science. Happy 2019, everyone!

Improving psychological theory-testing via “systems of orders”

My friend Julia Haaf has been killing it lately (follow her on twitter and check out her google scholar). She just finished her PhD at Missouri and took up a really cool postdoc at the University of Amsterdam, and it feels like every other month she is posting a preprint to some awesome new paper. One of her papers I’d like to highlight is titled “A note on using systems of orders to capture theoretical constraint in psychological science” (co-authored with Fayette Klaassen and Jeff Rouder), which she presented at APS 2018 in our invited symposium, “Bayesian methods for the pragmatic psychologist.”

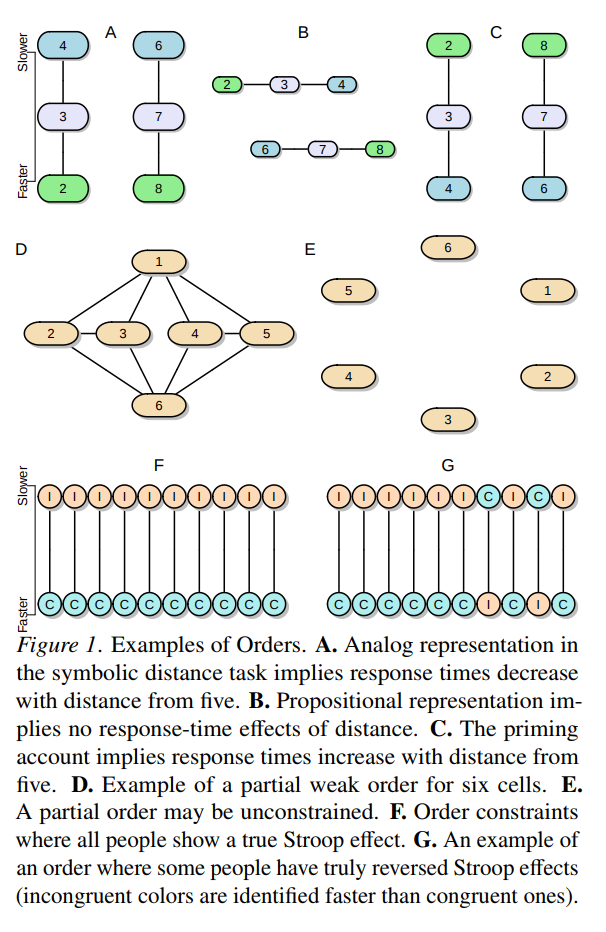

This paper really blew me away. One common theme in the ongoing reproducibility debate in psychology is that we need to improve the theory development of our field. The fact is, as psychologists we tend to describe our theories as a set of ordered relationships; e.g., that men respond slower than women in condition A but not condition B. I’m not sure if that will ever change. But when we go to test these directional theories, we usually do something super simple to account for our directional prediction, like a one-sided t-test. Julia and her coauthors describe this process as intellectually inefficient, because “by positing [a] coarse verbal theory that provides for only modest constraints on the data, we are neither risking nor learning much from the data.” We can do better.

The paper goes on to present a framework that allows us to represent these types of theoretical predictions as sets of explicit order constraints between parameters in a statistical model. Moreover, they demonstrate with nice examples how a Bayesian approach to comparing competing psychological models allows for richer tests of theories in psychology. And come on, just look at this figure. It’s awesome.

Should we go to the LOO for model selection?

Another person killing it lately is my friend Quentin Gronau (he isn’t on twitter but check out his google scholar page full of interesting work!). Quentin is doing his PhD at the University of Amsterdam, and he blogs at http://www.bayesianspectacles.org from time to time. He and I are at the same stage of our PhD (third year) and we have a lot of overlapping research interests, so I’m always eager to read any paper he writes. One of Quentin’s papers that came out last year that I found quite thought-provoking was titled “Limitations of Bayesian Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation for Model Selection” (co-authored with E.-J. Wagenmakers).

The main idea of this paper is to examine, in the simplest cases possible, the behavior of the Bayesian version of leave-one-out cross-validation (i.e., LOO) when used as a model comparison tool. It turns out that LOO does some weird stuff. For instance, consider comparing models of random guessing vs. informed responding (e.g., H0: θ=.5 vs. H1: θ≠.5) in some binary choice scenario. If we are in a situation where data come in pairs, and if it happens that every pair has 1 success and 1 failure, then we would ideally want our model comparison tool to give more and more evidence for the guessing model as pairs continue to come in. A split pair is, after all, perfectly in line with what the guessing model would predict will happen. If you use LOO for this model comparison, however, the evidence in favor of the guessing model can cap out at a relatively low amount even with observing an infinite number of success-fail pairs.

Also, look at these pretty figures. So damn clean.

The conclusion of this paper was, basically, be careful of LOO if you use it as model comparison tool; if it does weird stuff in super simple cases then how can we be confident it’s doing something sensible in more complex cases? (The paper is more nuanced of course). This paper created quite a stir among some Bayesian circles, and prompted the journal that published it, Computational Brain and Behavior, to invite some very prominent researchers to write commentaries, which I also found quite thought-provoking (find them here, here, and here, and a rejoinder here). All in all, this paper and the commentaries made me think deeply about model comparison tools and what we should expect from them.

Correlation, causation, and DAGs, oh my!

Another person I want to include in this post is my other friend named Julia: Julia Rohrer (you’ll follow her on twitter and on google scholar if you know what’s good for you). (Both Julias also happen to be German! Julia was apparently the 36th most popular women’s name in Germany in 2017. Wait, Quentin is German too. Wow, the education system over there must be doing something right.) Julia R. is also in her third year of her PhD –holla!– at the Max Planck Institute for the Life Course in Leipzig, where she is studying personality psychology. ALSO she is simultaneously(!) doing an undergraduate degree in computer science. Last year Julia published what I think is one of the best introductory tutorials out there on causal modeling, titled “Thinking clearly about correlations and causation: Graphical causal models for observational data.”

I think this paper should be required reading for anyone who wants to make causal statements but is limited to collecting observational data. A big challenge when working with observational data is that you can’t rule out confounding factors using randomization like you could in a controlled experiment. This paper outlines a way to model the relationships between variables of interest using what are called “Directed Acyclic Graphs” (i.e., DAGs) to get at the causal inferences we want to make in observational studies. If we create a set of boxes representing variables of interest and arrows that connect them, then if we follow certain rules, voilà, we have ourselves a DAG and maybe a chance at inferring causation. (There’s a bit more to it than just that, of course).

All the figures in this paper are box and arrow causal plots, so I’ll spare you copying them here. Instead I will share some section headers from this paper that I really enjoyed:

- Confounding: The Bane of Observational Data

- Learning to Let Go: When Statistical Control Hurts

- Conclusion: Making Causal Inferences on the Basis of Correlational Data Is Very Hard